This primer tutorial covers some of the Python basics of strings and characters. These skills will help build your cybersecurity skills and serve you well in competitions with the cyber:bot.

Strings are sequences of characters. For example, “ABC” is a string of characters. Computer software, apps, and Internet communication all depend heavily on strings. For example, much of the communication between browsers and servers over the Internet contains strings. These strings might contain Internet searches, GPS coordinates, text messages and more. Many of the messages you see on web pages and in apps also started as strings.

The Cybersecurity tutorials also rely heavily on strings to exchange radio messages between cyber:bot robots and other micro:bit modules. These strings may have packet data that could contain a code for a particular cyber:bot, navigation instructions, and even sensor values. They can be encrypted by the center and decrypted by the receiver to prevent misuse if intercepted by another team. So, later, you’ll use a micro:bit to send and another to receiver, but here, we’ll focus on the string and character basics using scripts that a single micro:bit will run.

You will need:

Complete these tutorials first:

You have skills with character and string basics you’ll use in upcoming tutorials for packetizing, parsing, encrypting, decrypting, and evaluating:

After this, you will also be ready to move on to the next tutorials:

A string is a sequence of characters. You are likely to see strings expressed in many different ways in Python scripts, so this page shows many of the formats you are likely to encounter.

It also introduces how strings can contain data. Because of this, Python has many features for manipulating strings. Examples include indexing, built-in functions, and string methods.

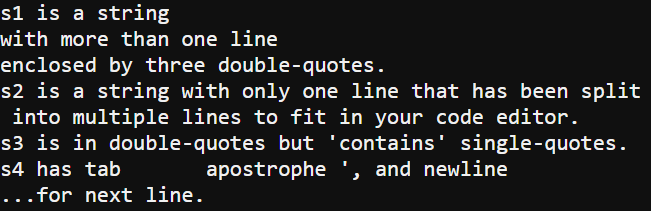

Strings can be enclosed in

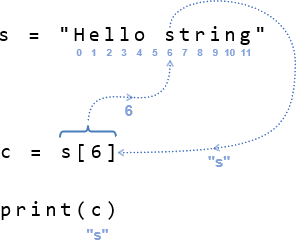

Strings with multiple lines have to be enclosed in either three single quotes or three double quotes.

Keep in mind that an apostrophe and a single quote are the same thing. But, two apostrophes ” are not the same as a double quote “. A double quote is inserted when you hold the Shift key as you type an apostrophe key.

'This is a string, enclosed by single-quotes.' "This is also a string, enclosed by double-quotes." '''This is also a string with more than one line enclosed by three single-quotes.''' """This is also a string with more than one line enclosed by three double-quotes."""

A single-line string can span multiple lines of code if each line is joined by the backslash \ character. One advantage to double quotes is that those strings can contain apostrophes.

"This is a string with only one line"\ "that has been split into multiple"\ "lines to fit in your code editor"\ "This string in double-quotes 'contains' single-quotes."

Strings can also contain special characters called escape characters. In general, escape characters are preceded by a backslash \ and are used to insert characters into a string that you cannot use just by typing them.

For example, a string enclosed by single quotes could not normally contain a single quote, but preceding it with a backslash, like this: \’ makes it possible. This string also has an embedded tab, single quote, and new-line:

'\t Tab, \' apostrophe, \n...and text on a second line.'

A single character, like an ‘A’ in quotes is a string object, even though all it contains is one character. Scripts sometimes start with an empty string that they add characters or strings to later. There are four examples of this empty string after the ‘A’ character.

'A' '' "" '''''' """"""

Strings do not necessarily have to be assigned to variables. For example, here is a string in a print statement that uses a string as-is:

print("This is a string without a variable reference.")

In many cases, it is better to name a string. If you use a long string more than once, naming it will save considerable code space. For example, instead of two print statements, a string is named once and printed twice:

s = "This is a string with a variable references: s." print(s) print(s)

Inside the micro:bit, characters are actually stored as numbers. In the case of the character A, it’s number is 65. The number for the B character is 66. The numbers are called ASCII codes, and are actually the numbers your keyboard sends your computer when you type the A, B, and other keys. Writing scripts that manipulate ASCII codes is a first step toward encrypting messages for cybersecurity.

You can find the ASCII Table for codes 0 to 127 in the Reference section:

Strings can contain characters that represent numbers. It is important to understand that a string with “1234” is very different from an int with a value of 1234 that you can add, subtract, multiply, etc. Instead, “1234” are just the characters that represent the numbers.

For example, take a string variable named s that contains the characters “1234”. The quotes make it a string. Without the quotes, n = 1234 creates an int variable that will work in calculations.

s = "1234" # this makes a string with characters n = 1234 # this makes an int variable with the value 1234

Radio and Internet devices often have to convert numbers to strings and add names before sending them to other devices. The devices that receive the string have to find the names and numbers in the string. In many cases, they also have to convert the string representation of the number back to an int or float so that it can be used in calculations. For example, here are two names and numbers:

s1 = "First number" n1 = 1234 s2 = "Second number" n2 = 5678

One script would have to assemble or packetize the string into this before transmitting:

s = "First number 1234 Second number 5678"

The script running in the receiver might have to parse this data. In this case, parsing would involve breaking the string into its four substrings: “First number”, “1234”, “Second number”, and “5678”. It might also be up to the receiver to find the “1234” and “5678” substrings and convert them back to int variables that the script can use for calculations.

Sending and receiving scripts might also have to encrypt the string so that nobody other receivers cannot figure out what the string contains. Here is a very simple example of an encrypted string. The transmitter would have to change each character in some way, and the receiver would have to change each character back to the original before it can process the data. Can you decrypt it and figure out what it really says?

s = "Ifmmp"

In Python, strings can also contain Python statements. For example, this string:

s = ""

print("Hello!")

print("Hello again!")

""

…can be sent from one micro:bit to another. The receiving micro:bit can actually execute the statements inside the string. This resembles how servers send code to computers to be executed in web pages. The web content and Javascript to respond when you click buttons are all sent from the server, to your client computer, and then executed by your browser.

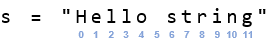

Each character in a string has an index number. That index starts at the first character, counting from zero.

For example, in s = “Hello string”, H has an index of 0, e has an index of 1, l has an index of 2, and so on, up through g with an index of 11. See how even the space between Hello and string is a character with an index?

Python has many tools for accessing, manipulating, and converting string information. Here is one indexing example where the 6th character ’s’ is copied to the c variable and then printed.

Python has built-in functions for certain string operations:

Additionally, strings that represent other data types can be converted to those types with built-in functions like int(), float(), dict(), list() and more. Example:

s = "123" # A string with numbers, but cannot be used in calculations n = int(s) # Convert to an int type n = n + 1 # The result can be used in calculations

The string class has many methods. Some return information about the string. Others return new strings that are changed versions of the originals, and there are also some that return different types of objects that contain the string’s characters. A few examples are shown below.

string = "This is a string. It is a sequence of characters!"

char_index = string.find("sequence") # returns index of first letter in sequence

new_string = string.replace("It", "A string") # replaces "It" with "A string"

char_list = list(string) # converts a string into a list

lower_case = string.lower() # converts string to all lower case

upper_case = string.upper() # converts string to all upper case

Let’s start with a script that creates a string, names it s, and prints it.

# first_string_intro from microbit import * sleep(1000) s = "ABC 123" print(s)

The statement s = “ABC 123” creates a string variable named s. The string it refers to contains the characters A B C 1 2 3. The statement print(s) displays the contents of the string named s.

A print statement allows you to display more than one string at a time. You will find it helpful to add a string that explains what’s about to be printed. So, instead of just print(s), you could use print(“s = “, s). This will become important when you write larger scripts. While adjusting them to work the way you want, you can include information such as the variable name and the location within the the script the print statement is being executed. Here is an example:

s = "ABC 123"

print("s =", s)

As mentioned earlier, strings can contain multiple lines.

"""This is also a string with more than one line enclosed by three double-quotes."""

A single line string can also be split up into multiple lines in the Python script.

"This is a string with only one line"\ "that has been split into multiple"\ "lines to fit in your code editor"\

A string in double quotes can contain single quotes:

"This string in double-quotes 'contains' single-quotes."

Strings can also contain escape characters preceded by a backslash to print special-case characters like the tab, apostrophe, and newline. Here’s an example you will try.

s4 = 's4 has tab \t apostrophe \', and newline \n...for next line.'

Keep in mind that if the above string was enclosed in double quotes, it would not need the \’ to display the apostrophe.

Let’s try modifying the script so that it displays s = ABC 123 instead of just ABC 123 in the terminal. That way, you’ll know that the terminal is displaying the contents of the s variable you created. This is very useful in a script that has many variables!

# first_string_try_this

from microbit import *

sleep(1000)

s = "ABC 123"

print("s =", s)

This script has some of the fancier strings that were discussed earlier. s1 is multiline, s2 is a single line that has been split across multiple lines in the Python editor. S3 is a string in double-quotes that contains a couple of single quotes. S4 has three escape characters, \t for tab, \’ for a single quote, and \n for the invisible character that advances the cursor to the next line.

# first_string_your_turn from microbit import * sleep(1000) s1 = """s1 is a string with more than one line enclosed by three double-quotes.""" s2 = "s2 is a string with only one line "\ "that has been split into multiple "\ "lines to fit in your code editor. "\ s3 = "s3 is in double-quotes but 'contains' single-quotes." s4 = 's4 has tab \t apostrophe \', and newline \n...for next line.' print(s1) print(s2) print(s3) print(s4)

Keep in mind that some of the lines might wrap depending on the width of the browser and possibly due to settings inside the terminal.

Each string is a sequence of characters, where each character is defined by a code number. For example, the string “ABC 123” is stored as a sequence of numbers: 65 65 66 67 32 49 50 51 66 49 50 51. These numbers are called ASCII codes. ASCII stands for American Standard Code for Information Exchange.

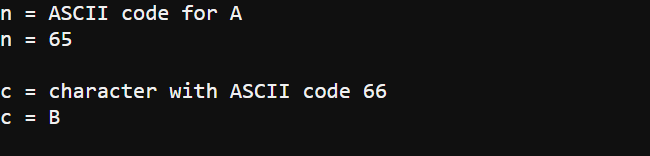

You can use Python statements to return the ASCII code of a character, and also to return the character for a given ASCII code. Let’s try that!

# chars_in_strings_intro

from microbit import *

sleep(1000)

print("n = ASCII code for A")

n = ord("A")

print("n =", n)

print()

print("c = character with ASCII code 66")

c = chr(66)

print("c =", c)

print()

The statement print(“n = ASCII code for A”) displays a heading to help give context to the messages below it.

print("n = ASCII code for A")

The function ord() returns the ASCII code of a string that contains a single character. The ASCII code for the character A is 65. So, ord(“A”) returns 65, and n = ord(“A”) stores the value 65 in the variable n.

n = ord("A")

After that, print(“n = “, n) displays “n =”, followed by the value of n, which is 65. Lastly, the print() just prints an empty line.

print("n =", n)

print()

Note: the ord() function only works if the string contains a single character! The MicroPython runtime doesn’t care whether you enclose characters in single or double-quotes, but single quotes for single characters are more readable. Consider “A” vs. ’A’.

After that empty line, print(“c = character with ASCII code 66”) prints another heading.

print("c = character with ASCII code 66")

The chr() function accepts an ASCII code, and returns that ASCII code’s character. So, c = chr(66) stores the character B in a variable named c.

c = chr(66)

Since c now stores the character B, print(“c =”, c) prints c = B.

print("c =", c)

print()

The variable name s is often used in scripts to name strings. In scripts where many string operations are performed, s might be used repeatedly as a temporary or working variable that ends up being many different strings, each for a brief period of time. Strings in the script that have important meanings should be given descriptive names. One example would be password = “abc123”.

The variable name c can often be found as the name of a string if it stores a single character.

A built-in function is one that’s always there in Python, no module importing required. For strings, Python has four important built-in functions:

The ord() and char() functions were just used in the last example script, and you will get to experiment with len() and str() in another activity.

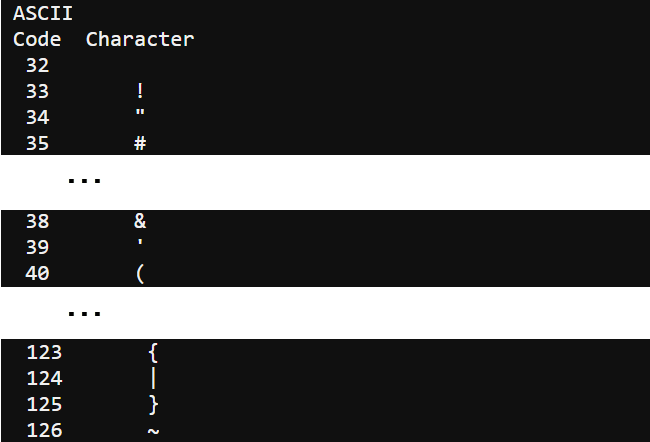

The first 32 ASCII codes are control characters intended for older printers and storage devices. Some of them are still used with terminals today. For example ASCII character 10, the line feed character, causes the Python terminal’s cursor to move down a line. In the previous activity, you used the escape sequence n to add the ASCII 10 to strings.

Printable characters range from 32 (space) to 126 (~). As you have seen from experimentation, the upper-case alphabet is codes 65 through 90, the lower-case alphabet is 97-122, and digits are 48-57.

Imagine a script that repeatedly calls the chr() function inside a for… loop. The first time, it prints chr(65), the second time, it prints chr(66), and continues all the way through chr(90). What do you think you’d see?

# chars_in_strings_try_this

from microbit import *

sleep(1000)

for n in range(65, 91):

c = chr(n)

print(c)

sleep(250)

You can print your own list of printable ASCII characters with the next example script.

# chars_in_strings_your_turn

from microbit import *

sleep(1000)

print("ASCII")

print("Code Character")

for n in range(32, 127):

c = chr(n)

print(n, " ", c)

sleep(250)

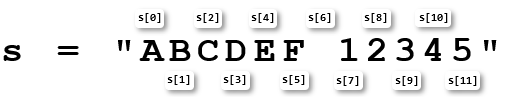

Some scripts you will write for cybersecurity encryption and decryption will need to access each character in a string. As a warmup for this, let’s try a script that checks and displays a certain character in a string.

# char_access_intro

from microbit import *

sleep(1000)

s = "ABCDEF 12345"

print("Fifth character in s:")

c = s[5]

print("c = s[5] =", c)

print()

The string s is “ABCDEF 12345”. The string name, followed by a positive index value in square brackets, returns the character at that location in the string. The index starts with A at s[0], B is at s[1], and so on up to the character 5 at s[11]. You can also use -1 through -12 to index characters from rightmost to left.

If your script uses an index that’s larger than the string, it’ll cause an exception. To find out how many characters are in a string, Python has that built-in function called len() that returns the number of characters in a string. Your script can check a string’s length, then can then use that result in indexing when accessing characters in that string, so that it never tries to access an out of bounds character. This is especially important when each character is indexed in a loop.

Before indexing all the characters in a string, let’s use len() to verify that there are 12 characters in the string.

# char_access_try_this

from microbit import *

sleep(1000)

s = "ABCDEF 12345"

print("Characters in s:")

length = len(s)

print("length =", length)

print()

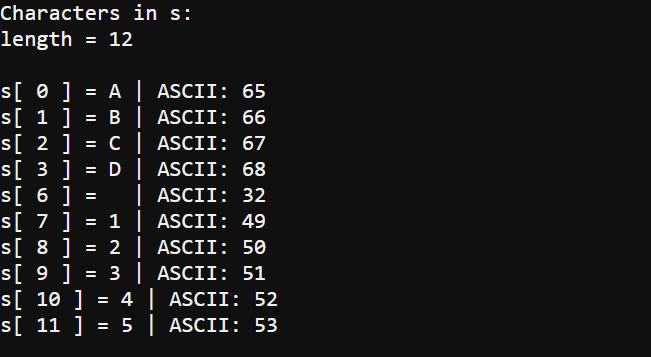

Now that your script can access the length of a string, it can use that number to limit how many characters the script checks in a loop. This makes it possible to access every character safely, without accidentally using an index value that’s too large.

This script displays both the individual characters in the string along with their ASCII codes.

# char_access_your_turn

from microbit import *

sleep(1000)

s = "ABCDEF 12345"

print("Characters in s:")

length = len(s)

print("length =", length)

print()

for n in range(length):

c = s[n]

a = ord(c)

print("s[", n, "] =", c, "| ASCII:", a)

print()

In cybersecurity situations, your script might need to modify a string it receives. One method for modifying strings is to create a larger string by adding smaller strings together. This process is called concatenation.

# string_surgery_intro

from microbit import *

sleep(1000)

s1 = "Have "

s2 = "a "

s3 = "nice "

s4 = "day."

s = s1 + s2 + s3 + s4

print("s = ", s)

The script starts with 4 separate strings: s1, s2, s3, and s4, and addes them together. Addition with string objects is very different from the addition in the int and float objects you are probably familiar with. When string objects are added, they are combined. So, “abc” + “def” results in a string “abcdef”. In our case, s = s1 + s2 + s3 + s4 results in a new string variable s that refers to the “Have a nice day.” string.

In the previous activity, a single character was accessed using an index, like c = s[3]. Your scripts can also view segments of strings by using a range instead of a single index number in the square brackets.

Let’s say you have a string named s:

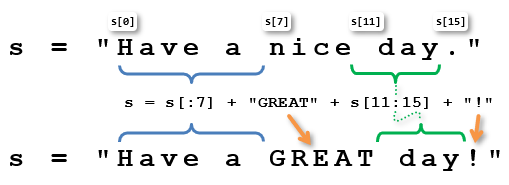

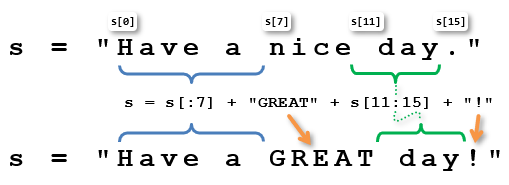

In Python-speak, strings are considered immutable. Being immutable means that once created, a string cannot be changed. That doesn’t mean that s = “Have a nice day.” cannot be changed to s = “Have a GREAT day!” It just means that the original “Have a nice day.” string cannot be changed. A statement can still grab parts of “Have a nice day.” and use them to create a new string that reads “Have a GREAT day!” The resulting string can even be assigned back to s.

s = "Have a nice day." # BEFORE s = s[:7] + "GREAT" + s[11:15] + "!" s = "Have a GREAT day!" # AFTER

The s variable starts as this string: “Have a nice day.” The second line adds “Have a ” + “GREAT” + ” day” + “!”. See how “Have a “ is s[:7] from the original string? Add the string “GREAT” to that, and then ” day” with a leading space, which is s[11:15], and lastly add “!”, and the string surgery is complete!

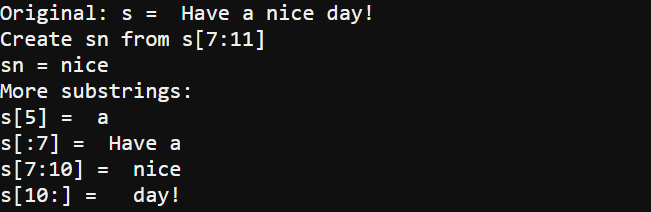

This script starts with “Have a nice day.” and then creates a new string sn with the “nice” portion of the original. After that, it demonstrates some more ways to access segments of an original string that were introduced above.

# string_surgery_try_this

from microbit import *

sleep(1000)

s = "Have a nice day!"

print("Original: s = ", s)

sn = s[7:11]

print("Create sn from s[7:11]")

print("sn =", sn)

print("More substrings:")

print("s[5] = ", s[5])

print("s[:7] = ", s[:7])

print("s[7:10] = ", s[7:11])

print("s[10:] = ", s[11:])

The original string: s = Have a nice day!

Create sn from s[7:11] sn = nice

More substrings:

s[5] = a

s[:7] = Have a

s[7:10] = nice

s[10:] = day!

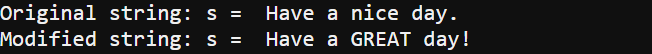

Now that we can concatenate strings with + and access substrings, let’s make a script that starts with “Have a nice day.” and uses parts of it to create “Have a GREAT day!” It’s the equivalent of substituting “GREAT” in place of “nice” and “!” in place of “.”

As you work with this script, keep in mind that the original string “Have a nice day.” was never changed. A new string was created using parts of the original and then assigned equal to s, redefining s.

# string_surgery_your_turn

from microbit import *

sleep(1000)

s = "Have a nice day."

print("Original string: s = ", s)

s = s[:7] + "GREAT" + s[11:15] + "!"

print("Modified string: s = ", s)

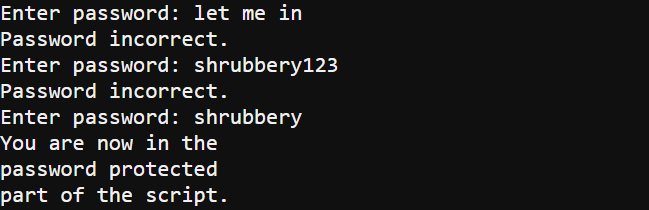

Sometimes, a script needs to check a string for an exact match. If it’s not an exact match, the program won’t continue! Password protection is an example of this.

Other times, a script might need to ignore strings that don’t contain a certain substring. For example, a radio-broadcasting micro:bit might send names with different ID strings and commands. Each micro:bit can be running a script that looks for its own ID string and only take action if it detects it in the string.

# comp_find_check_intro

from microbit import *

sleep(1000)

password = "shrubbery"

while True:

s = input("Enter password: ")

if(s == password):

break

else:

print("Password incorrect.")

print("You are now in the")

print("password protected")

print("part of the script.")

A string variable named password is declared as “shrubbery”.

password = "shrubbery"

Inside a while True loop, the first step is to prompt the user (that’s you) for a password. The result you type is stored in the variable s.

while True:

s = input("Enter password: ")

Next, an if…else… statement checks if the input you typed, which is stored in s, matches the password variable. The if… statement uses the equal to == operator, which returns True if the two strings match, or False if they don’t. When the two strings do match, the break statement “breaks out of” the while True loop and moves on to the password-protected part of the script. When it doesn’t match, the script just displays “Password incorrect.” After that, the while True loop repeats.

if(s == password):

break

else:

print("Password incorrect.")

The script only reaches this point if the user typed the correct password..

print("You are now in the")

print("password protected")

print("part of the script.")

Sometimes it’s wise to check if a string contains a certain phrase. For example, a micro:bit might be sending radio commands to more than one cyber:bot robot. A unique name could be used to select which cyber:bot in the group should execute the command.

The string.find() method can help with this. It returns the index of the first character in the matching substring. If it returns 0, it means it found the character at the very beginning of the string. If it returns 5, it means it started at the fifth character in the string. If it doesn’t find a match, it returns -1.

Here are some examples of how string.find() can be used:

Keep in mind, you can also search for characters. Just use a single character in the search, like s.find(“A”).

As mentioned in the Strings and Characters page, string objects also have useful methods. Here are a few examples to try:

new_string = string.replace("substring", "replacemnt_string")

lower_case = string.lower()

upper_case = string.upper()

new_list = string.split()

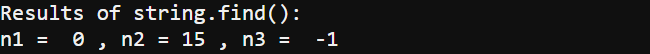

Here we have three examples of searching for substrings with string.find(). After finding the index of the first and second instances of one substring, it looks for a substring that isn’t there. Examine the searches and results carefully.

# comp_find_check_try_this

from microbit import *

sleep(1000)

s = "Arthur: It is 'Arthur', King of the Britons."

n1 = s.find("Arthur")

n2 = s.find("Arthur", 7, len(s))

n3 = s.find("Lancelot")

print("Results of string.find():")

print("n1 = ", n1, ", n2 =", n2, ", n3 = ", n3)

Does this make sense? The first instance of “Arthur” starts at character 0 in s. The second starts at 15. Since Lancelot isn’t in there, it returns -1.

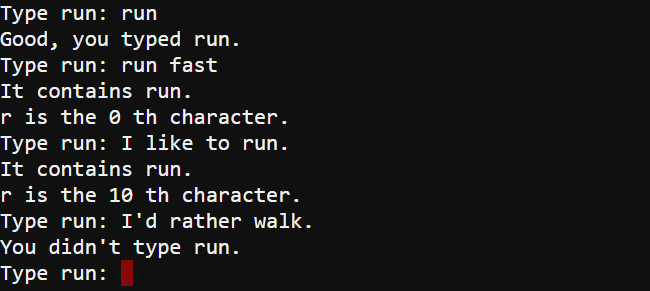

Sometimes a script has to make the distinction between an exact match and the presence or absence of a term in a string. Even if string.find() returns 0, that doesn’t prove that there aren’t more characters following the match. One way to solve this is to use the is equal to == operator to check if the string is an exact match. If it isn’t, then use the string.find() method to check if the substring is anywhere in the string.

# comp_find_check_your_turn

from microbit import *

sleep(1000)

while True:

s = input("Type run: ")

n = s.find("run")

if(s == "run"):

print("Good, you typed run.")

elif(n != -1):

print("It contains run.")

print("r is the", n, "th character.")

else:

print("You didn't type run.")

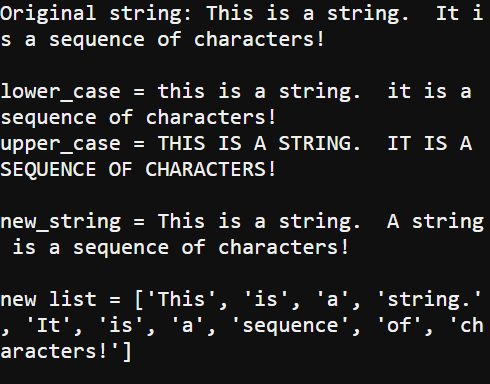

This example program introduces four more useful string methods: replace(), upper(), lower(), and split().

# other_methods_intro

from microbit import *

sleep(1000)

string = "This is a string. It is a sequence of characters!"

print("Original string:", string)

print()

lower_case = string.lower()

upper_case = string.upper()

print("lower_case =", lower_case)

print("upper_case =", upper_case)

print()

new_string = string.replace("It", "A string")

print("new_string =", new_string)

print()

new_list = string.split()

print("new list =", new_list)

print()

The first routine declares a string, names it string, and then prints it for reference.

string = "This is a string. It is a sequence of characters!"

print("Original string:", string)

print()

The string.lower() and string.upper() methods return lower and upper case versions of the original string, and print them:

lower_case = string.lower()

upper_case = string.upper()

print("lower_case =", lower_case)

print("upper_case =", upper_case)

print()

The string.replace() method is another way to replace parts of a string. It’s not as straightforward as the approach from the previous String Surgery section, because it would replace all instances that matche the substring, if there were more than one “It”.

new_string = string.replace("It", "A string")

print("new_string =", new_string)

print()

The string.split() method splits a string with separators into substrings. By default, the separator is a space, but you could pass it a comma, for example. Many data strings are comma delimited, and need to be split before each individual data item can be examined.

new_list = string.split()

print("new list =", new_list)

print()

In the case of string.replace(“It”, “A String”) in the previous example script, there was only one instance of it, so it worked as expected. Unlike the approach from String Surgery, the string.replace() method replaces all instances of a substring by default. So, if you’re not careful, and choose a substring like “a”, you might see some surprising results!

The string.replace() method does have an optional argument to limit the number of replacements it makes in the string.

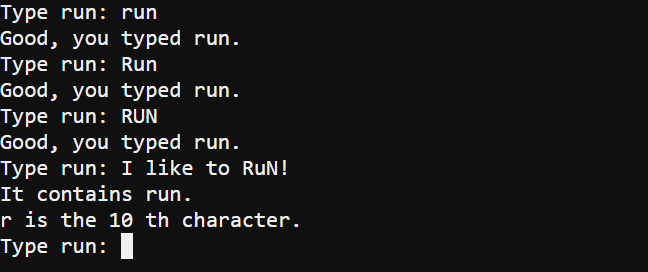

One use for the string.lower() method is to make menu systems accept whatever the user types, regardless of what combination of uppercase and lowercase characters have been used. This can be helpful in menu systems, because we might just want the script to do what it’s told, regardless of whether we typed run, RUN, Run, RUn, or some other combination. By calling string.lower() first, it makes it so the program only has to check for one word: run

This next example is a modified version of comp_find_check_your_turn from Compare, Find, Check. By adding a single string.lower() call, we can avoid checking for every conceivable combination of run, Run, RUN, RuN, etc.

# other_methods_try_this

from microbit import *

sleep(1000)

while True:

s = input("Type run: ")

s = s.lower() # <- Add this line

n = s.find("run")

if(s == "run"):

print("Good, you typed run.")

elif(n != -1):

print("It contains run.")

print("r is the", n, "th character.")

else:

print("You didn't type run.")

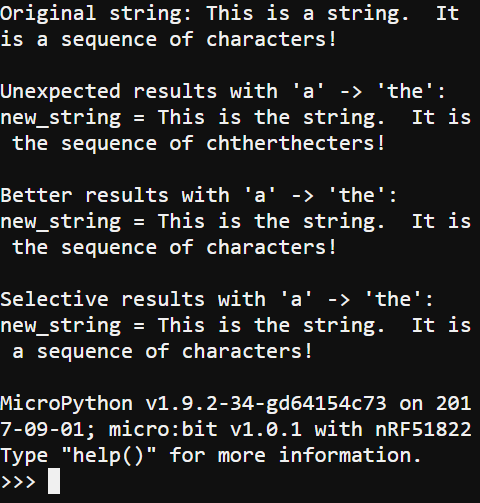

As mentioned on the previous page, the string.replace() method is designed to find and replace all parts of a string that match the substring. If there’s only going to be one match, great. What if you instead want to replace the word “a” with “the” though?. If the original string contains the word “characters”, it might get converted to “chtherthecters”. Yikes!

To solve this, the substring could be set to ” a “ with spaces before and after. Likewise, the replacement string is should be ” the “, also with spaces before and after.

And let’s say you only want to replace the first instance of “a”. Another approach would be to use string.replace(” a “, ” the “, 1).

# other_methods_your_turn

from microbit import *

sleep(1000)

string = "This is a string. It is a sequence of characters!"

print("Original string:", string)

print()

new_string = string.replace("a", "the")

print("Unexpected results with 'a' -> 'the':")

print("new_string =", new_string)

print()

new_string = string.replace(" a ", " the ")

print("Better results with 'a' -> 'the':")

print("new_string =", new_string)

print()

new_string = string.replace(" a ", " the ", 1)

print("Selective results with 'a' -> 'the':")

print("new_string =", new_string)

print()

When the micro:bit receives strings from other devices, it may need to convert them to other data types to process their data. For example, one micro:bit might use a string to transmit a list of int values. The transmitter has to convert its int values to string representations before sending. The receiver will have to convert the string representations of integers back to int values before it can use them in calculations.

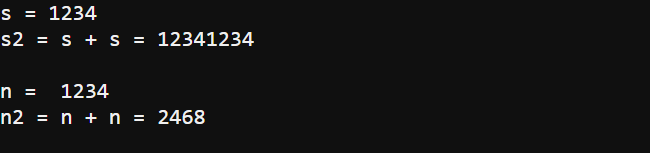

Before converting from int to string and back to int again, let’s look at just how differently they behave with an operator that can be used with either type.

# convert_intro

from microbit import *

sleep(1000)

s = "1234"

n = 1234

print("s =", s)

s2 = s + s

print("s2 = s + s =", s2)

print()

print("n = ", n)

n2 = n + n

print("n2 = n + n =", n2)

print()

Python recognizes the intended data type when you initialize a variable, based on format.

s = “1234” creates a variable named s of type string, note the enclosing double-quotes.

n = 1234 creates a variable named n of type int; note the lack of double-quotes. (There’s no decimal point, so it’s not a float.)

The plus + operator performs integer addition on int variables, and so n2 = n + n mathematically adds the two 1234 integers for a result of 2468.

In contrast, that + operator will concatenate two strings—in other words it will join them together. That is why s2 = s + s resulted in “12341234”.

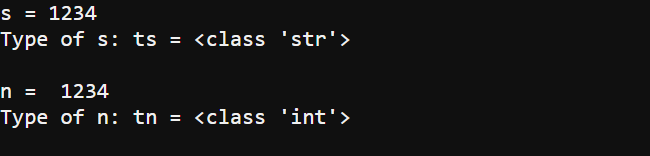

Let’s try changing some statements to check the data types of s and n. This can come in handy when you want to want your script to know for sure what it is receiving from another device.

# convert_try_this

from microbit import *

sleep(1000)

s = "1234"

n = 1234

print("s =", s)

ts = type(s) # <- change

print("Type of s: ts =", ts) # <- change

print()

print("n = ", n)

tn = type(n) # <- change

print("Type of n: tn =", tn) # <- change

print()

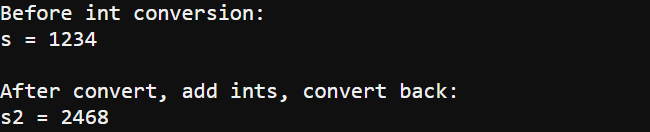

You may have already seen how to get a string and convert it to int in the Computer–micro:bit Talk tutorial. Here, the int result after calculations is also converted back to a string.

# convert_your_turn

from microbit import *

sleep(1000)

s = "1234"

print("Before int conversion:")

print("s =", s)

print()

n = int(s) # convert to int

n2 = n + n # add

s2 = str(n2) # convert back

print("After convert, add ints, convert back:")

print("s2 =", s2)

Strings can contain Python expressions, or even one or more Python statements. So long as those strings are passed to the correct functions, an incoming string can be evaluated as an expression or even executed as one or more Python statements!

Security heads up! If you are going to set up an app that can run scripts you can type in, you will also have to make sure that only you and others with permission can send text with embedded scripts to your app!Let’s start with evaluating an expression that’s in a string.

# embed_intro

from microbit import *

sleep(1000)

s = "1 + 2 + 3 + 4"

reps = eval(s)

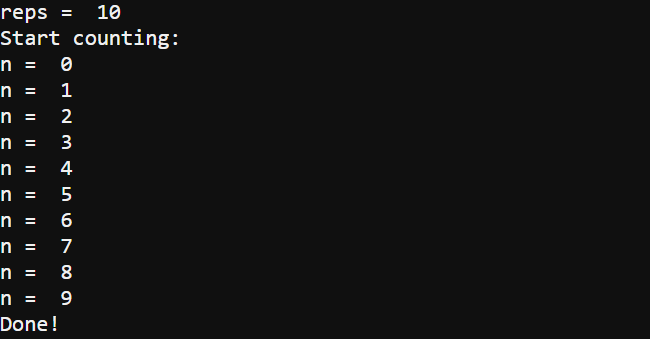

print("reps = ", reps)

The script starts with the string s = “1 + 2 + 3 + 4”. Then, eval(s) evaluates 1 + 2 + 3 + 4 as a Python expression and returns 10. Since reps = eval(“1 + 2 + 3 + 4”), the result of 10 is stored as an int in reps.

While Python’s built-in eval() function is for evaluating expressions embedded in strings, its exec() function can actually execute Python statements.

Remember that a string that starts and ends with triple-quotes “” can span multiple lines!

Let’s try adding statements contained in a string, and then executing them with the exec() function.

# embed_try_this

from microbit import *

sleep(1000)

s = "1 + 2 + 3 + 4"

reps = eval(s)

print("reps = ", reps)

s = "" # <- add

print('Start counting:') # <- add

for n in range(0, reps): # <- add

print('n = ', n) # <- add

"" # <- add

exec(s) # <- add

print('Done!') # <- add

A script that can run Python scripts embedded in strings opens up a lot of possibilities. Cybersecurity activities rely heavily on a computer-connected micro:bit that radio-transmits strings with commands to a remote cyber:bot. Since scripts can be embedded in strings, it might be possible for you to update your cyber:bot robot’s script on the fly! One challenge will be to prevent hackers from doing that to your cyber:bot for their own reasons!

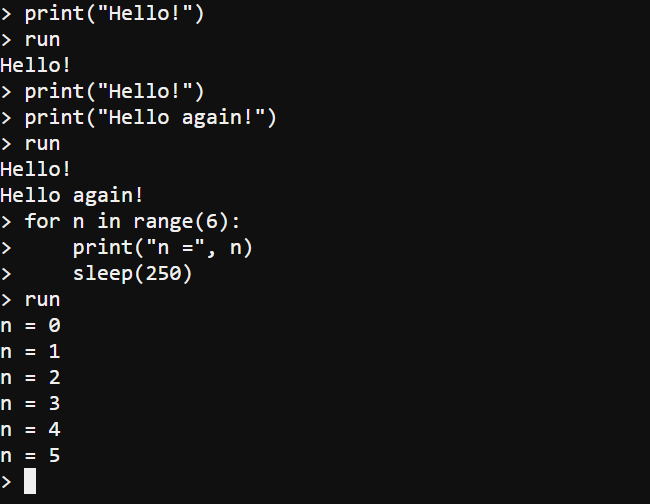

This simple script accepts Python statements that you enter. After you have entered the last Python statement, type run and press Enter to execute the script.

# embed_your_turn

from microbit import *

sleep(1000)

s = ""

t = ""

while True:

s = input("> ")

if(s != 'run'):

t = t + s + "\n"

else:

exec(t)

t = ""

Did each different script you entered execute in the terminal?

The script starts by creating empty strings named s and script. The s string receives each line you type, and the script string stores the actual script consisting of all the statements you type.

s = "" script = ""

In the main loop, the s variable prompts for input from you by displaying a > prompt. When you type a Python statement and press Enter, that statement gets stored in s.

while True:

s = input(“> “)

The if…else… statement checks to see if what you typed does not match the string “run”. When it does not match, it assumes you have typed a statement and uses script = script + s + “\n” to append your statement and add a newline character to any previous statements you might have typed.

if(s != 'run'):

script = script + s + "\n"

When you do type run and press Enter, the exec(script) function call runs the Python script you typed. Then script = “” sets the script variable to an empty string so that you are starting over with an empty script.

else:

exec(script)

script = ""